Killer Tomatoes Read online

Page 2

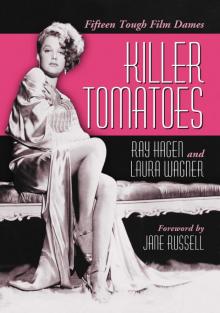

Portrait of Lucille Ball, 1944.

Her Goldwyn contract was coming to a close and she asked for and got a release. “I didn’t want to be a showgirl any more,” she said later. “I wanted to get on with it and I had a chance to be a contract player at Columbia, although I was making a lot less money than I did as a showgirl.” Columbia was only a slight improvement. Lucy appeared in comedy shorts and more bits. Her stay at the studio was abruptly cut short, says Lucy, when “one day at six o’clock they fired about 15 of us. We were out lock, stock and barrel. We were on the street. We just stood there. What happened? Nobody knew.”

In need of work, she reluctantly heeded RKO’s call for girls with modeling experience for Roberta (1934). It was only a dress bit, but the studio was sufficiently impressed by her looks—blonde, very lean and lanky—to sign her in late ’34. “I was a stock girl at RKO,” she wryly told a reporter later. “Down in the small print it said I had to sweep out the office if they wanted me to.”

At first there wasn’t much change. The bits were no different than the ones Lucy had handled earlier. Momentum was gained when Lela Rogers, Ginger Rogers’ mother, took an interest. According to Ginger, her mother, who conducted acting classes at RKO, intervened on Lucy’s behalf. “The studio told my mother they were thinking of letting Lucy go. My mother said firmly, ‘You fire Lucy … then I’ll quit. Lucille Ball is one of the most promising youngsters on this lot. If you’re stupid enough to do that, the minute you let her go, I’ll snap her up and take her to another studio and see that she gets the roles she deserves.”

The studio listened, probably not in fear of losing Lela Rogers but, more likely, Ginger, one of the top stars at RKO at that time. Lucy’s roles built in prominence. Her early parts presented her as a rough-around-the-edges, sometimes bitchy blonde. At least the size of her roles was improving.

RKO gave her permission to star in the stage musical comedy Hey Diddle Diddle, opening in Princeton, New Jersey, on January 21, 1937 with Conway Tearle. Variety praised “her sense of timing,” but the show never made it to Broadway due to Tearle’s health, and closed a month later in Philadelphia. This disappointment was tempered by producer Pandro S. Berman’s interest in Lucy’s comedic abilities. He wanted her right away for Stage Door (1937), a revamped version of Edna Ferber and George S. Kaufman’s play.

Stage Door was an important turning point for Lucy, her snappy flippancy adding immensely to the diversity of showbiz hopefuls at the boarding house.

Co-star Ann Miller became a good friend, always crediting Lucy with getting RKO to sign her. In her autobiography she remembered the set being “very friendly,” despite “quite a lot of tension between Ginger Rogers and Katharine Hepburn. Lucy helped relieve a lot of the strain because she would always laugh and joke and kid. Eve Arden was the same way, and thank God for them.” Miller added to writer Eve Golden that Lucy “was a wonderful lady, loads of fun. She was like a showgal, you know, that great, rare sense of humor.”

After the good response she drew from Stage Door, Lucy languished in uninteresting supporting parts and her first lead, opposite Joe Penner, in Go Chase Yourself (1938).

What gave her a boost was The Affairs of Annabel (1938), just another product from RKO’s B-unit. Everyone was surprised when this congenial spoof of the movie world became a breakout hit.

Ball plays movie star Annabel Allison for Wonder Pictures (“If It’s a Good Picture—It’s a Wonder”), long-suffering victim of her press agent’s (Jack Oakie) wild schemes to get her publicity. Still smarting from his previous gag to promote her last picture, Behind Prison Bars, by getting her arrested, the put-upon actress is hired out by Oakie as a maid in preparation for A Maid and a Man. The Affairs of Annabel was Lucy’s first chance to really show how well she could handle light comedy. Two months later, Annabel Takes a Tour (1938) was released, with the same popular response. RKO envisioned a series, but the idea was nixed when Oakie demanded more money than the B-budget could handle.

The studio suddenly got serious on her in 1939, casting her in four straight dramas. The soapy saga Beauty for the Asking was about a jilted girl rising to cosmetic queen. Twelve Crowded Hours was a newspaper yarn with Richard Dix; considering their age difference (Dix, 44, Ball, 28), the two were surprisingly agreeable together. RKO reteamed them the next year in The Marines Fly High.

At first glance Lucy’s role in Panama Lady, originated by Helen Twelvetrees in Panama Flo (1932), doesn’t seem to fit the normally spirited Ball, but she gave an effectively subdued performance. Lucy once referred to this South American–set drama as “a dog,” but the New York Daily News regarded it as a “minor triumph” for her, even if box office proved otherwise.

The part of the hardboiled floozy in Five Came Back was pure Lucy, at this point in her career anyway. Considered a sleeper, the tense film maintains its rep today. With this success, Lucy earned the right to climb out of the second feature trenches, but no go. RKO gave her what amounted to a cameo in Kay Kyser’s That’s Right—You’re Wrong (1939).

In December 1939, Orson Welles began work on his first movie, one which never reached fruition. Before his classic Citizen Kane, he was keen on The Smiler with a Knife, a thriller Welles thought, after rewrites, had the makings of The Thin Man. He first wanted Carole Lombard, but she declined. He was intrigued by the possibility of casting Ball, but faced opposition from RKO, who didn’t feel she could carry the picture. Which just proved she was at the wrong studio. This was con-firmed most eloquently by her casting in the turkey You Can’t Fool Your Wife (1940).

Not since her supporting days at RKO had she handled a role as bitchy as Dance, Girl, Dance (1940), mopping the floor with Maureen O’Hara in the process. Lucy is a burley queen (singing “Mother, What Do I Do Now?”), with an attitude as plain as her name: Tiger Lily White. The movie itself, however, is notable today solely for introducing her, in an indirect way, to Desi Arnaz.

She had just finished filming a scene with O’Hara. Desi, in Hollywood to reprise his stage role in Too Many Girls, later remembered, “The first time I saw Lucy was in a Hollywood studio lunchroom. Lovely, dazzling Lucille Ball was to be one of the stars of Too Many Girls. I was eager to meet her. Then she walked in. She had a black eye, frowzy hair and was wearing a too-tight black dress with a rip in it. She had been playing a dance-hall floozy in a free-for-all fight scene. I groaned, ‘Oh, no!’ That afternoon, when she showed up on the set where I was working, I said, ‘Oh, yes!’ She had fixed her hair and make-up and put on a sweater and skirt. She was a dream. I took one look and fell in love.”

Lucy broke off her longtime relationship with director Alexander Hall, saying it wasn’t love at first sight when she met Desi, “it took a full five minutes.” The whirlwind courtship cumulated just after Too Many Girls premiered when the couple was wed on November 30, 1940, in Greenwich, Connecticut.

Before this, however, RKO had paid $100,000 for the screen rights to Too Many Girls. When Mary Martin refused the role, played on stage by Marcy Westcott, Lucy was penciled in, with Trudy Erwin ghosting on vocals. Employing members of the theater cast, and retaining the show’s director (George Abbott), the movie added Frances Langford and Ann Miller.

The movie revealed a likable Lucy at her most relaxed. She plays the headstrong daughter of Harry Shannon, making him suspicious when she insists on going to his alma mater Pottawatomie, all the way out in Stop Gap, New Mexico. He hires four All-American football players to monitor her, and, of course, she falls in love with one of them (Richard Carlson). The plot was threadbare and a bit silly, but fast-paced, filled with “youthful effervescence and spontaneity” (Variety), and a score by Rodgers and Hart (“I Didn’t Know What Time It Was”).

She tested for Howard Hawks’ Ball of Fire (1941) with Gary Cooper, but lost out to Barbara Stanwyck. After this major disappointment, Lucy starred in the zany A Girl, a Guy and a Gob (1941). “The important thing,” wrote The New York Times, “is not who gets the girl, but how much fun they h

ave along the way,” which summed up the amiable story nicely. This underrated comedy wasn’t a high point in her career, but an improvement over some of the stuff RKO was giving her.

Valley of the Sun (RKO, 1942) was one of Lucy’s better RKO films. “The prettiest girl in Arizona,” she gets involved with attractive Indian agent James Craig.

And it was much better than Charlie McCarthy-Edgar Bergen’s Look Who’s Laughing (1941); it was material like this Lucy wanted to break free of. Valley of the Sun (1942), a comedy Western directed by old hand George Marshall, was better. It was RKO’s most expensive ($650,000) Western since Cimarron (1931). Top-billed Ball (“The prettiest girl in Arizona”) is engaged to unscrupulous Indian agent Dean Jagger, until attractive Indian scout James Craig shows up.

Andy Warhol called The Big Street (1942), based on Damon Runyon’s story Little Pinks, “the sickest film ever made,” and he isn’t far off-target. At first, Lucy, who won the part over suggested star Merle Oberon, was concerned about the unsympathetic nature of her character, a nightclub singer with a mean streak as wide as the Grand Canyon. She consulted Charles Laughton because she considered her role “so bitchy. It’s so unrealistically rude, crude and crass.” But Laughton allayed her fears: “My advice to you is to play the bitchiest bitch that ever was! Whatever the script calls for. And don’t try to soften it. Just play it!” She definitely did.

Lucy plays a gorgeous, self-absorbed singer (her song “Who Knows?” is dubbed by Martha Mears), worshiped by clearly sadomasochistic busboy Little Pinks (Henry Fonda), whom she treats like a doormat. “Her Highness,” as Fonda calls her, doesn’t lack for admirers but she’s after cash, adoration and position, in the whole package of William T. Orr.

She snaps, growls and snarls at Little Pinks—“that’s not a name, that’s a toothbrush”—but he moons and swoons over her. More so when jilted Barton MacLane knocks her down stairs, leaving her crippled. Here, it gets even sicker.

Fonda pays her hospital bills, goes into hock, cares for her, caters to her every whim—while Lucy insults and taunts him. Then she decides on a change of climate; with no money to travel, Lucy suggests—this is the kicker—that Fonda push her wheelchair the more than one thousand miles to Florida. And he does it.

But Lucy’s performance isn’t just that. She shows that some of her nastiness stems from her uncertainty of ever walking again, allowing the facade to break down for … just … a … few … seconds … then—wham, she’s back in the groove, treating everyone like dirt. Her death scene is very affecting. Credit Lucille Ball for making a heartless shrew a figure of pity at the conclusion.

Lucy called her character “a girl with a foolish, unhealthy obsession which made her more ruthless than Scarlett O’Hara. It was anything but a sympathetic part, but it was exciting because it was so meaty—so rich in humor, pathos and tragedy.” It was anything but a hit.

Nor was shooting helped by the coolness between her and Fonda. “I didn’t know Henry Fonda all that well before we began The Big Street, and I sure didn’t want to know him all that well when we were finished. He hardly talked to me the whole time, and when he did, well…”

One problem was the scene where Lucy learns for the first time that her legs are paralyzed. “The director [Irving Reis] and I rehearsed the scene. I started swaying my shoulders, and tried dancing with only my arms. I try to make my legs move, but they won’t. I’m dancing, sitting up in bed, looking at my paralyzed legs. Irving was terrific. He said that I had done it perfectly and he wanted to shoot it right away while we still had the mood. I looked over to the door, and Fonda was standing there. He had watched the rehearsal, and as soon as Irving started setting up the shot, he came over to me and said, ‘You’re not going to do it like that, are you?’ I said, ‘Well, Irving said it was good.’ Fonda just shook his head back and forth and walked away. Try to do a scene after that.”

Louella Parsons talked her up as Oscar-worthy, but it never happened. At RKO it meant nothing. They thought her salary ($1500) unwarranted. Her films were doing poorly and she was refusing movies, like a loan-out to Fox for the Betty Grable musical Footlight Serenade (1942). With the bust of The Big Street, it was clear: Lucy was out.

Lucy’s first for MGM, the Technicolor musical DuBarry Was a Lady (1943) with Red Skelton, was also the first with her soon-to-be-famous red hair, courtesy of hair stylist Sydney Guilaroff.

As her last picture under contract, she replaced Rita Hayworth in the musical comedy Seven Days Leave (1942). All was not happy on the set. Victor Mature, dating Hayworth at the time, made his displeasure over the casting known. It was a shaky time, not only because of the contract termination, but because of Desi’s absences traveling with his band.

If RKO failed to recognize her abilities, MGM was more than willing to sign her. It was MGM, by way of hair stylist Sydney Guilaroff, who would change her career. She was elevated to full-fledged star in bigger-budgeted productions, with Technicolor only enhancing her beauty. As for her blonde (sometimes brown) hair: “I felt she needed to stand out,” related Guilaroff in his autobiography, “so I mixed a variety of hair-dyes into a henna rinse that transformed her into a shimmering golden redhead.”

First at MGM was DuBarry Was a Lady (1943), an Arthur Freed production adapted from the smash 1939 Cole Porter show starring Ethel Merman. Of course, Lucy was no Merman; she was dubbed on the title song (Martha Mears again), but sang with her own voice on “Friendship.”

Red Skelton is smitten with money-conscious Ball, asking her to marry him after he wins the lottery, with only Gene Kelly standing in their way. Red plans on slipping Kelly “a Rooney”—“a high-powered Mickey”—but mistakenly drinks it himself. He’s dreamily transported to France where he’s King Louis XV and Ball is his mistress Madame DuBarry.

As singer May Daly, Lucy is serious and practical, trying to suppress her love for penniless Kelly, while he croons Cole Porter’s lovely “Do I Love You, Do I?” But in Red’s dream, her manner changes: she’s wacky, sassy, visibly in love with “The Black Arrow” (Kelly). She’s also hell bent on keeping Red at arm’s length, especially during their romp “Madame, I Love Your Crepes Suzettes.” The dance suddenly becomes a mad chase, with Red and Lucy flopping down exhausted at the end. “This ain’t a love affair,” he sighs. “This is a track meet.”

DuBarry Was a Lady proved to be a major hit for MGM.

Working with producer Arthur Freed again, Lucy copped the lead in Best Foot Forward (1943), another Broadway hit, from originally slated Lana Turner; Lana had to bow out due to pregnancy. Lucy plays herself, a Hollywood star asked by Winsocki Military Academy student Tommy Dix to be his prom date. She accepts, through the prodding of her press agent William Gaxton, and things get a little crazy.

Ball is at her wry best, flipping the insults and quips left and right, at what she correctly perceives to be a bad situation. In need of a new contract, she reluctantly plays along. Envisioning huge crowds mobbing her as she steps off the train, Ball looks over the deserted station with disgust. “Well, I don’t mind the band playing,” she notes sarcastically, “but if this crowd doesn’t stop shoving, I’ll scream.” One lone barking dog greets her. “My public,” Lucy regally gestures.

Best Foot Forward’s script was teeming with wisecracks, certainly better than anything RKO gave her, and she made the most of them. She also gets to “sing” again, this time with Gloria Grafton’s voice, on “You’re Lucky,” written for the film by the Broadway composers Hugh Martin and Ralph Blane.

Movie star Lucy wants out of her press agent William Gaxton’s ploy to get her publicity by being a prom date in Best Foot Forward (MGM, 1943).

Her luck ran out with Meet the People (1944). It was a strange concept for a musical: factory worker Dick Powell co-writes a musical play about “the common man,” wanting glamorous Broadway actress Lucy to star. But even after she becomes a shipyard worker, only the “common man” can put on his play; wealthy Lucy must humble herself to matter in Powell’s

life. “The hero is the people,” songwriter-producer E.Y. Harburg explained. “The story takes the point of view that the people, after all, are running the country.” It was all a lot of hooey, far too preachy to appeal to musical fans. Lucy looks gorgeous, but she and staid, pretentious Powell (who sings “In Times Like These” superbly) were not a good match.

She next did three cameos in a row. In the all-star Thousands Cheer (1943), she joined Ann Sothern and Marsha Hunt in an unfunny skit about a barber (Frank Morgan) posing as a doctor giving physicals to potential WAVEs. Lou Costello, eluding studio police, invades the movie set where Lucy, Preston Foster and director Robert Z. Leonard are shooting a fictional movie in Abbott and Costello in Hollywood (1945).

Most famous, for sheer camp value, is Ziegfeld Follies (1946, filmed in 1944). In the opening number “Here’s to the Girls,” sung by Fred Astaire, newcomer Cyd Charisse’s ballet bit gives way to an exquisite Lucy on top of a live merry-go-round horse, stunning in pink. After gracefully moving around the stage, she pulls out a whip and “lashes” a group of female dancers dressed as cats. Costumer Helen Rose later remarked, “I created lavish outfits of pink sequins, using twelve hundred ostrich feathers. With Lucille Ball’s flaming red hair, I thought it was the best number in the picture.”

MGM bought Philip Barry’s 1942 play Without Love, which had starred Katharine Hepburn and Elliott Nugent on Broadway, as a vehicle for her and Spencer Tracy. To Barry’s displeasure it was rewritten for the screen by Donald Ogden Stewart, and to Tracy’s displeasure the movie was stolen by the supporting players: Lucille Ball and Keenan Wynn. After her lavish Technicolor movies, she was there mainly to supply comedy asides in a black-and-white movie, and she did her job. This was a sure sign that her days at MGM were numbered.

Killer Tomatoes

Killer Tomatoes