Killer Tomatoes Read online

Contents

Acknowledgments

Foreword by Jane Russell

Introduction

1. Lucille Ball: Red Ball Express

2. Lynn Bari: The Other Woman

3. Joan Blondell: Trouper

4. Ann Dvorak: A Life of Her Own

5. Gloria Grahame: Those Lips, Those Eyes

6. Jean Hagen: After the Rain

7. Adele Jergens: A Lot of Woman

8. Ida Lupino: Triumph of the Will

9. Marilyn Maxwell: The Other Marilyn

10. Mercedes McCambridge: Inner Fire

11. Jane Russell: Body and Soul

12. Ann Sheridan: Oomph Without Ego

13. Barbara Stanwyck: The Furies

14. Claire Trevor: Brass with Class

15. Marie Windsor: Face of Evil

Bibliography

Index of Terms

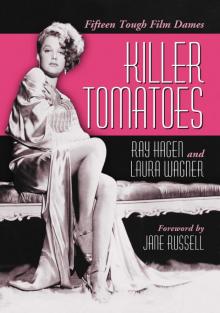

Killer Tomatoes

Fifteen Tough Film Dames

Ray Hagen and Laura Wagner

Foreword by Jane Russell

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina, and London

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Hagen, Ray, 1936–

Killer tomatoes : fifteen tough film dames / Ray Hagen and Laura Wagner ; Foreword by Jane Russell

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7864-1883-1

1. Actresses—United States—Biography.

I. Wagner, Laura, 1970– II. Title.

PN1998.2.H345 2004

791.4302'8'092273—dc22 2004013463

British Library cataloguing data are available

©2004 Ray Hagen and Laura Wagner. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Cover photograph: Publicity shot of Ann Sheridan in 1939

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

For all my Barbaras

—Ray Hagen

To my mentor, the late Doug McClelland, for his brilliance, friendship and encouragement and to

My Mother. Unlike Marie Windsor in The Killing, I’d never sell you for a piece of fudge

—Laura Wagner

Acknowledgments

RAY HAGEN: My sincerest gratitude to Jane Russell for patiently spending so many hours answering so many questions, and for being the first person in many years to call me “kiddo.” Also to her close friends and co-workers—Beryl Davis, Connie Haines, Hal Schaefer, Jack Singlaub and the late Portia Nelson—for helping me add so much to Jane’s story.

To the family and friends of Jean Hagen (no relation) who went out of their way to help me tell Jean’s story: her children, Aric Seidel and Christine Seidel Burton; her sister, LaVerne Verhagen Steck; and “the Northwestern girls” who became her friends for life—Patricia Neal, Nathalie Brown Thompson, Mimi Morrison Tellis, Helen Horton Thomson and Nancy Hoadley Salisbury.

To Peter Bren for taking the time to give me new and important information about his loving and beloved stepmother, Claire Trevor.

To the ladies with whom I lunched all those years ago: Mercedes McCambridge in 1963, Ann Sheridan in 1966 and Jean Hagen in 1975. I tried to pass myself off as a distinguished film scholar but they knew I was just a star-struck nervous wreck in the presence of a Goddess. And speaking of the 1960s …

To my old friend Jean Barbour for allowing me to raid the back issues of her late husband Alan G. Barbour’s wonderful Screen Facts magazine, where my interview with Ann Sheridan was first published in the November 1966 issue (vol. 3, #2), and where the earliest version of my Gloria Grahame article was published in May 1964 (vol. 1, #6).

To editors Leonard Maltin (Film Fan Monthly) and the late Henry Hart (Films in Review) for giving us fellow movie freaks a place to write about and an excuse to meet our movie icons whilst cleverly disguised as grown-ups. (Did we ever fool anyone?) My first attempts at profiling Jane Russell, Claire Trevor and Mercedes McCambridge appeared in, respectively, the April 1963, Nov. 1963 and May 1965 issues of Films in Review. An early profile of Jean Hagen was in Film Fan Monthly, Dec. 1968. Those pieces were the genesis of my chapters on these ladies in this book.

To Colin Briggs, Bob Robison and Jeff Gordon for their help with my Lynn Bari chapter.

And of course to comely Laura Wagner, first for getting me into this, and then for helping to get me out of it.

LAURA WAGNER: Thanks are due to the friends who put up with my insane demands for information and movies: Mida Baltezore, John Cocchi (The Credit King), Christine Corsaro, Earl Hagen, G.D. Hamann, Richard Hegedorn, Frances Ingram, David Marowitz, Marvin of the Movies, Jim Meyer, James Robert Parish, Bob Robison (ACCOLADES), Morty Savada, George Shahinian, Eleanore Starkey, Charles Stumpf, Dan Van Neste and Tom Weaver.

To those who consented to interviews: George Dean, Marsha Hunt, Sybil Jason, Virginia Mayo, Lina Romay, Jack Smith, Martha Tilton and George Ward.

To all my photo dealers through the years: Gene Massimo (of Fan*Fare), Hal Snelling, Milton T. Moore, Jr., Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store and Larry Edmunds Bookshop (Mike Hawks).

To Steve Tompkins. This poor man uncomplainingly sent me tons of videos, even trading with others to get me my needed films. His friendship is much appreciated.

To Christina Rice, creator of the fabulous AnnDvorak.com website, who was of immeasurable help with the Dvorak chapter. Christina, you are my hero.

To the late Barbara Whiting-Smith, bless her, who was not only a terrific actress, but also a terrific person.

To Ben Ohmart, always ready to be supportive.

To Bob King, my editor at Classic Images (where an abridged version of my Marilyn Maxwell essay appeared in the February 2000 issue) and Films of the Golden Age, who was the first to give me a chance. He deserves special mention; no one could ask for a nicer editor or a funnier guy to chat with. His colleague at CI, my buddy Carol Peterson, is funny, indispensable—and one tough dame.

To Ray Hagen, who made this project maddening but fun. His shrewdness, editing, humor and Barbara Stanwyck impersonations are unmatched.

To my family: my wonderful mother, Frances Wagner, who is consistently my best audience, but never much of a critic. Which is a good thing. I’d be lost without my brother, Tom Wagner, a whiz at finding photos and information. He always comes through, and I treasure him. My nephews, Jake and Luke Vichnis, are the lights of my life, even if they’re too young to read this book. And to my outrageous aunt, Charlotte Rainey, who bears a striking resemblance to Ida Lupino. How cool is that?

Last, and certainly never least, my great pal, the late Doug McClelland, the finest film writer ever. From the moment I met him, he was my guiding star. In the last months of his life he was there helping, as usual, and lending support to a project he believed in. He said this would be the one movie book he “was looking forward to.” I hope we didn’t disappoint him.

Foreword

by Jane Russell

When I was a kid I adored Katharine Hepburn, especially when she played Jo, the ballsy sister in Little Women. All the kids in school started calling me “Jo.” I also loved Barbara Stanwyck, Ann Sheridan, Bette Davis, Claire Trevor—I didn’t know them but after seeing them in so many movies, I felt like I knew them. They weren’t feminists, they were just strong women, and I always admired anyone who had some guts. All those sweet, quiet, polite, ladylike little things just bored me to death.

Back then there were

so many wonderful women’s stories being filmed, and so many strong actresses. But by the time I started doing movies they were mostly making men’s stories. It has always saddened me that I never got to work with directors like George Cukor and William Wyler, directors who could really pull such marvelous performances from actresses. For example, I’d love to have played Lillian Roth in I’ll Cry Tomorrow. She wanted me to play her, but they decided to go with Susan Hayward instead. So many of us were typecast then and that was hard to fight. I was usually “the girl in the piece” and it was the guys’ stories, but I was always the gal with a smart answer.

That was fine with me because I was used to holding my own in the company of guys; it was second nature to me. My cousin Pat and I grew up as the only two girls among twelve boys, including my four younger brothers, and we raised them. I understood boys, and I understood men. I was married to a football star, Bob Waterfield, and there were always guys around the house. So I guess I had an advantage over many women who weren’t raised around men and didn’t understand them, because the movie business was run by men—studio heads, directors, most of the writers. If you couldn’t handle these guys on an equal footing, you weren’t going to last very long in pictures.

Why were these strong actresses, and the characters they played, so popular? Why are women like that popular when you know them? Well, maybe not the really tough ones, the killers, but even they’re interesting to watch. Sometimes even Barbara Stanwyck was too nasty, but I liked her so much.

I love the idea of a book about strong women and I’m so glad it’s here.

Introduction

The only way to conquer Barbara Stanwyck was to kill her, if she didn’t kill you first. Lynn Bari wanted any husband that wasn’t hers. Jane Russell’s body promised paradise but her eyes said, “Oh, please!” Claire Trevor was semi-sweet in Westerns and super-sour in moderns. Ida Lupino treated men like used-up cigarette butts. Gloria Grahame was oversexed evil with an added fey touch—a different mouth for every role. Ann Sheridan and Joan Blondell slung stale hash to fresh customers. Ann Dvorak rattled everyone’s rafters, including her own. Adele Jergens was the ultimate gun moll, handy when the shooting started. Marie Windsor just wanted them dead. Lucille Ball, pre–Lucy, was smart of mouth and warm as nails. Mercedes McCambridge, the voice of Satan, used consonants like Cagney used bullets. Marilyn Maxwell seemed approachable enough, depending on her mood swings. And Jean Hagen stole the greatest movie musical ever made by being the ultimate bitch. These wonderwomen proved that a woman’s only place was not in the kitchen. We ain’t talkin’ Loretta Young here.

When movies began to talk in the late 1920s, the women talked back (and snarled back and slapped back and shot back), and audiences adored them. Tough guys and tougher gals quickly replaced the suave sweeties of the silent era as a new, slangy form of screen acting catapulted truckloads of brand new and mostly stage-trained actors to screen stardom. The wisecrack had entered its golden age. Sound suddenly made the saucy flirtations of Clara Bow, the lugubrious vamping of Theda Bara and the imbecilic innocence of Mary Pickford seem instantly dated and even laughable, and they were replaced in the public’s affections by actresses who behaved and sounded like actual people (even as they continued to look heavenly beyond all reason).

Some of the ladies in this book were among the very first wave of muscular maidens who set patterns that are being copied to this day. These hot tamales weren’t dependent on men to get where they wanted to go, though they weren’t above pretending to be if necessary. They’d been through a mill or two and they’d learned the ropes.

(Oddly, one of the most popular on-screen professions for these babes was not the first one that comes to mind, but that of singer. Cinematographers lingered lovingly over these Circes in gorgeous gowns, impeccably coiffed and made up, crooning seductive torch songs—dubbed if necessary, but who cared? Singing was apparently a code occupation for women of dubious ambition and, though one might question the connection, it made for some fabulous visuals.)

By 1933 Mae West had come on the scene and things had gotten so out of hand that bluenoses in general, and the Catholic Church in particular, were threatening boycotts if the movie studios didn’t clean up their act. There had been a Production Code all along but now it was put solidly into effect. There were still plenty of unwed mothers and gun-totin’ seductresses but now they had to pay for their sins. Impurities now had to be artfully suggested rather than shown, so the world would be safe for Shirley Temple.

Then, in the ’40s, film noir created a sensation and the ladies of noir were certainly no ladies. It wasn’t called film noir then, it wasn’t called anything, they were just detective movies or whodunits or mysteries, and the women were as strong as the men. Often, deliciously, stronger.

We offer here 15 femmes fatale from the late 1920s to the early 1950s, roughly the first quarter-century of American sound films. All played their share of heroines and housewives, but they really caught fire when the gutsy parts came along. Conspicuous by their absence here are Bette Davis and Joan Crawford, who have been written about so extensively that there isn’t a single word left to say about them. (Surprisingly, you won’t even find Ruby Keeler here. After all, who knows what was going on behind that blank stare?) We’ve included a number of big stars here but we also wanted to celebrate the careers of some lesser known actresses who, along with the superstars, helped to define the genre.

There were many other hard-boiled Hollywood hotties, of course, but with only so much time and space we had to whittle the list down to a precious few. And it must be grudgingly admitted that a wee tad of personal preference dictated not a few choices.

So here they are, a gaggle of highly skilled and utterly unique actresses whose pre-feminist strength and independence were awesome to behold. Whether with gags, glares or gats, they railed, they ranted, they raved, they rode roughshod. They ruled.—R. H. and L. W.

Lucille Ball: Red Ball Express

by LAURA WAGNER

Pretty Lucille Ball, who was born for the parts Ginger Rogers sweats over, tackles her “emotional” role as if it were sirloin and she didn’t care who was looking.—Critic James Agee on The Big Street (1942)

“I regret the passing of the studio system,” Lucille Ball once said. “I was very appreciative of it because I had no talent. Believe me. What could I do? I couldn’t dance. I couldn’t sing. I could talk. I could barely walk. I had no flair. I wasn’t a beauty, that’s for sure.” Most people agree with Lucy’s assessment of her film career. The millions of fans who still watch her, via reruns, on I Love Lucy, believe the character she played on the popular comedy—crazy about breaking into show business, yet possessing none of the talent required.

She’s such a TV icon it’s hard for some to separate the two Lucys—the gorgeous, snappy actress of film and the wacky, slapstick queen of television. On TV she was a middle-aged housewife, on film she was a dazzling beauty. The difficulty with her movie career wasn’t that she was bad or not up to the roles. Quite the contrary: They were rarely up to her.

She was born Lucille Desiree Ball on August 6, 1911, in Jamestown, New York. Her father, Henry Ball, was a telephone lineman, and her early childhood was spent in Butte, Montana, and Wyandotte, Michigan. Henry died in a typhoid epidemic when Lucy was three, so her mother, Desiree (nicknamed DeDe), expecting her second child (Fred), worked in a factory to support her family. It was there she met Ed Peterson, who would become her second husband in 1918. The whole family eventually settled in with DeDe’s father in Celoron, New York.

Lucy went from organizing shows in high school to attending the Robert Minton–John Murray Anderson School of Drama in Manhattan in 1926. The star pupil was an 18-year-old Bette Davis. Lucy, homesick and out of her league, quickly returned home. Financial troubles there led her to venture back to New York City. She auditioned in vain as a showgirl for Earl Carroll and Florenz Ziegfeld. Instead she found luck in modeling, dropping out of school.

Th

e Player’s Club, Jamestown’s theater group, gave Lucy a supporting role in Within the Law in 1930. By all accounts she was a hit, and moved with the show when it played the Chautauqua Institution, a summer resort.

Even with this small-town success, Lucy concentrated instead on her modeling (for Hattie Carnegie, among others). It took prompting from agent Sylvia Hahlo to lead a reluctant Lucy into film. There was a call for models to go to Hollywood to appear in producer Samuel Goldwyn’s Roman Scandals (1933), starring Eddie Cantor. Feeling sure there was no hope for her at the auditions, convinced she was “the ugly duckling of the lot,” she was, to her surprise, hired for the six-week shoot. Lucy would meet actress Barbara Pepper, an enduring friend, during filming.

She secured a contract with Goldwyn lasting six months. She attributed this to her “stick-to-itness.” She told Kathleen Brady in 1986: “Suddenly I was in show business. It interested me because I was learning, and because I was learning I never complained. Whatever they asked, I did. I did one line, two lines, with animals, in mud packs, seltzer in the face. Eddie Cantor noticed it first at Goldwyn. He’d say ‘Give it to that girl, she doesn’t mind.’ I took it all as a learning time.”

The platinum blonde Ball was thought during this early period to resemble Constance Bennett, a fact which contributed to Goldwyn signing her, and she doubled for the star in Moulin Rouge (1934). Lucy was being paid around $300 a week as “atmospheric background” for Goldwyn and loan-outs to Fox.

Killer Tomatoes

Killer Tomatoes